Native-Art-in-Canada has affiliate relationships with some businesses and may receive a commission if readers choose to make a purchase.

- Home

- Native Women

Native Women

Their Roles and Their Influence

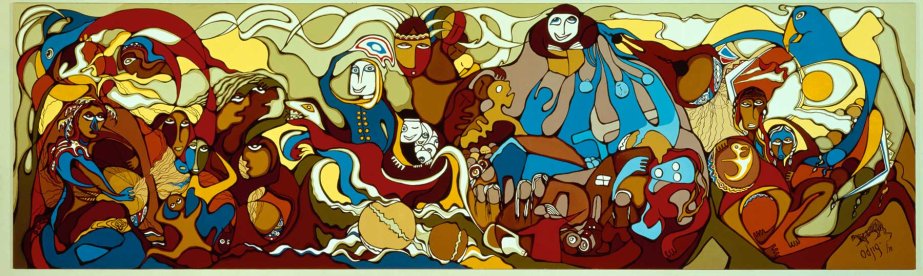

Daphne Odjig - "The Indian in Transition"

Daphne Odjig - "The Indian in Transition"Traditionally the roles of native women included child rearing, homemaking and healing. . . like women the world over.

They had limited

influence in spiritual leadership or in the decision process with

regards territorial expansion and defense. Even in the Iroquoian

matriarchal society, men were the community's leaders. . . with the kicker that they were elected by the women. But North America is a big continent with many,

many cultures so there was a great deal of variation from culture to culture, community to

community.

Women nowadays may bristle at the idea that their female ancestors weren't able to participate in all aspects of their societies but those were different times. It wasn't as if the family could get up in the morning and open the fridge to see what was on the breakfast menu. There was no fridge. Someone, literally, had to bring home the bacon. Someone, literally, had to keep the home fires burning. Gender roles allowed the family, the community and society as a whole to be fed, clothed, have a home to sleep in and a system of defense that could spring into action when necessary.

I'm not an anthropologist so I can't tell you much about the lives of native women other than what I saw and experienced over the last eight decades in my own Ojibwa culture. So I'll do that.

Marriage and Ojibwa Women

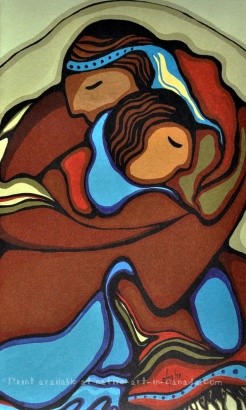

Moment of Commitment - by Daphne Odjig

Moment of Commitment - by Daphne OdjigIn my day, women (men, too) lived in their parents home until they made the decision to marry. Ojibwa women could decide for themselves who would be their life's partner but parents had a good deal of influence when push came down to shove.

If a father was adamant that a certain young man was an unsuitable match for his daughter, but the couple persisted, the issue might be formally presented to the respective clan leaders for their opinion. At that point the couple still had final say but there were circumstances when there might be reasons for parents to take their concerns to Dodem - a gathering of all the clans - and then whatever ruling came down was "the law" so to speak.

Here's a real life example which might sound to you like the beginnings of a fairy tale, but it's all true.

A young man from the Navajo reserve in the States had set off on an adventure to see the world. Although his father was Navajo, his mother was Dene and he had made his way to northern Canada to visit her people. Rather than take the short route back to his own reservation he decided to do "the circle tour" and see more of the country before he headed home. He eventually found himself in Ojibwa territory and, wouldn't you know, fell in love with a sweet Ojibwa maiden who lived in my community 200 miles north of Lake Superior.

The couple wanted to get married.

Her Daddy was concerned. After all, what did anyone really know about the guy? Maybe he was running away from something bad.

The girl's father wouldn't agree to the union. That didn't mean the couple couldn't marry, it just meant that there would be hard feelings to deal with unless they moved elsewhere. The family decided to take their problem to the Dodem when it met in the Fall.

The young fellow was invited to be present and state his case.

For him it must have been a daunting experience and looking back I realize that it said much about his character and his feelings towards his lady love that he would put himself through the ordeal.

When the seven clans gathered, each group had a specific place to sit around the fire. Hundreds of people were present. Slowly, one clan at a time, the father explained that the young man wanted to marry his daughter and that he was opposed because he didn't know enough about the fellow's character or circumstances in life. He wanted the considered opinion of each of the clans.

Now this process took a great deal of time. Each clan member had the right to question him about anything under the sun. In practice it was usually only the pertinent issues that were queried . . . what was his clan association, how did he plan on supporting the young woman, where did he expect to live, did he want to formally become a member of the community? But human nature got involved and the questioning got down right nosey and personal! I'll spare you the details because I know you aren't a nosey person and don't listen to gossip.

In the end he was granted permission to marry but there was a looooooong discussion about where he would sit around the fire.

The Navajo clan system is very different from the Ojibwa system and there was no clan association on the mother's side because the Dene didn't have a system of governance that involved clans. He couldn't be formally welcomed into the community without being associated with a clan, so what to do?

In the end they made him a member of the Marten clan. The reasoning was that the Marten clan members were "the helpers". Marten children had been taught from childhood that whenever they saw a situation that might benefit from an extra pair of hands it was their responsibility to step in and offer assistance. Any community can benefit from a few more Martens!

Native Women Were in Charge of the Home

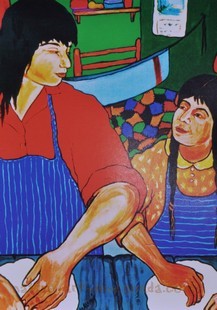

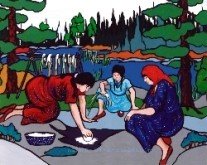

In my high school days boys took 'shop' and girls took something labelled 'domestic science'. I think native women could have written the book on the latter. With no electricity, no running water, no indoor plumbing, little money and no store close by anyway, generations of Ojibwa women fed and clothed their children using the resources that were available. Look at the background of the picture. See the blanket hanging from a couple of ropes over the bed? That's the cradle where the babies slept close to Mom so that she could tend them at night.

Summers were short and winters were long in the forests north of the Great Lakes. The whole land mass known as the Laurentian Shield was scraped bare of soil in the last ice age and what soil there is now is sparse and shallow. It's definitely not farming country. But the land provided food, shelter, clothing and medicines for generation upon generation of Anishnabe families.

We actually had it good in my day because with some effort we could go to a store and buy a few things that mainstream society took for granted - flour, pots, pans, tin dishware, knives, guns, sewing materials, lanterns and the fuel to keep them lit. Grandma had lived her life with very few of those supplies and her grandmother none at all.

Food for the Table

Nokomis painting - Drying Meat

Nokomis painting - Drying MeatGirls learned from their mother's and their grandmothers how to forage for food or for plants that could be made into medicines. They learned how to butcher the animals their fathers and brothers brought out of the bush and they learned how to preserve the meat.

Smoking meat over a slow fire removed the moisture and the smoke acted as a preservative. Canning wasn't really an option because transporting heavy glass sealers miles through the bush would have been asking for trouble.

We dried berries out in the sun - fighting off the birds all the while - and stored them in old lard pails or tobacco cans for use in the winter.

Most of the bulrush plant is edible . . . even the cattail if you harvest it in the early summer when it's still hard and before it goes to seed. Try slicing it thinly and gently sauteing it in butter. Yum. Mom used to dry the roots then grind them to a powder to make a type of flour. It wasn't good for baking but could be used to thicken gravy or add bulk to a soup. But the roots can be eaten raw, too. Wash them well and take a bite. They have a texture somewhat like a cucumber but the taste is different. AND...there's twelve times more vitamin C in a bulrush plant than there is in a single orange...so put that in your pipe and smoke it!

Mom and my grandmother also made a syrup from the sap of the birch trees. . . not quite as sweet as maple syrup but maples didn't grow in our neck of the woods so we were happy to go with what was available.

Clothing for the Family

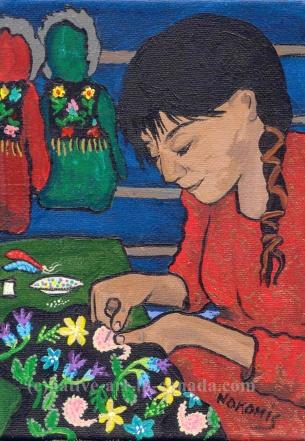

Nokomis - Beading the Jacket

Nokomis - Beading the JacketMy great grandmother and her mother would have limited access to fabric and modern sewing materials, but though the choices were limited my own mother had only go to the corner store . . . a Hudson's Bay post more than twenty five miles away.

The churches in that community often had second hand clothes they would sell or give away and Mom altered them to fit her growing brood. She made our jackets from old coats by carefully ripping them apart at the seams then cutting them down to fit whoever needed a new jacket that year. When she sewed the pieces back together she would reverse the fabric so that the fresh nap was on the outside and the worn fabric was on the inside. She did the same with the coat linings but then added the little detail that kept us alive . . . deer chamois between the outer fabric and the inner lining in the front, back and in the sleeves. Without the soft chamois that stopped the wind going through the stylish coats from mainstream Canada, we would never have survived the winters.

Mom always bought black velveteen from The Bay store to use to embellish our winter coats and to make beautiful tikinogans (back carriers) for the babies.

Did I mention that all this was done by hand with a simple needle and thread?

The Healing Hand

Here's where I'm going to fail you. By the time I was a teenager I was attending a high school in mainstream Canada. That would have been the time I would have started learning everything there was to know about the medicinal properties of the plants growing in our part of the world. I regret not paying more attention to the bits that I was shown in my younger years.

Anyway ... I'll share what I can remember.

I'll start by dropping the bomb that I was five years old when I participated in my first birth.

We were trained from a very young age in what to do to help a woman in labor just in case we were the only ones available. There was a good chance that would be the case. We had no neighbors and Dad was often gone for days hunting for meat or weeks in the winter on the trap line.

Notice I said I was five when I first "participated". At that age we sat in the room with the woman in labor and the woman who was helping with the delivery and we were talked through the whole process. They might have us "participate" in several births before we got over the "Yikes!!!" reaction and had enough presence of mind to be useful.

Deaths were handled in the same way.

The only other thing I can recall about health care issues is that we used a water plant to sooth toothache. We called it rat root because the muskrats loved to eat it. I have no idea what the common English name of the plant is let alone the botanical name. Made into a paste, it was rubbed on the sore gum which immediately went numb.

Oh! Another thing about tooth care. We didn't have toothbrushes but we broke off twigs from a little bush that will also have to go nameless and chewed them. The twigs shredded and must have done a good job of cleaning my teeth because I didn't have a cavity until I was a teenager in the city. By then, of course, I had access to the dread sugar!

And before I forget, here's the link to my favorite story. It about my first trip to the dentist.

Some Thoughts About the Equal Rights Issue

There's some truth to the stereotype of women being dominated by the men in their life and we modern women (not just native women, but all women in industrialized countries) wouldn't be where we are today if it wasn't for a few powerful women who were the exceptions to the rule.

I can't confirm what did or didn't happen in the relationships between long dead Ojibwa women and their partners...I can only speak of a few incidents that I recall from my own childhood. When they occurred I didn't take notes...I just made unconscious decisions about whether or not a woman's opinion is worthy of consideration.

As women, the most important thing we can do for children - boys as well as girls - is to trust our selves and take a stand for a future of equality.

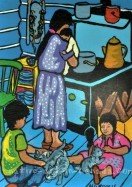

I learned that my opinion as a woman counted for something when one summer, I watched a whole community move that stove

you see in the picture. Read the story. They had to move it for miles along a footpath

that wound it's way over the great Laurentian Shield. There was no

option...my mother insisted. Given the attitudes of the day it's interesting to note that the folks moving the stove weren't Ojibwa - they were the white guys.

And in a world where it seemed there could be no possibility that women had a chance at financial freedom, I learned that where there's a will there's a way.

But the life of an Ojibwa woman of my generation wasn't all bravado. It was a simple life. It involved childbirth, child rearing, cooking, cleaning, and fun. Sometimes life worked, sometimes it didn't.

But here we are...you and me...both thinking about the contributions and the sacrifices that men and women in our own lives made to get us where we are today.