Native-Art-in-Canada has affiliate relationships with some businesses and may receive a commission if readers choose to make a purchase.

Canadian Aboriginal Art

A Voice Emerged From the Wilderness

Alle Sapp - Hauling Wood

Alle Sapp - Hauling WoodIn the aesthetic sense, Canadian aboriginal art didn't occur as a concept until the midpoint of the twentieth century. Petroglyphs, pictographs, pictoforms and totem poles hadn't been created for artistic reasons. That imagery was simply a powerful reminder of the spiritual reality of First Nation's people.

First Nations artists like Allen Sapp, Gerald Tailfeathers, Francis Kakige and Daphne Odjig had been painting and drawing since the 1940's and 50's (and for all you and I know other unrecognized souls may have been doing the same thing) but there wasn't a viable market for their work. Their efforts gave personal satisfaction but few opportunities to exhibit - let alone earn income to make a significant living.

For most of the last century museums displayed only prehistoric work and functional native art - masks, totem poles, bead and quill work, etc. Although at the same time, some galleries were selling off identical items as quickly as they could get their hands on them. But they were marketed as unusual artifacts, not as art. Even Inuit art was in it's infancy.

Morrisseau Changed Canadian Aboriginal Art

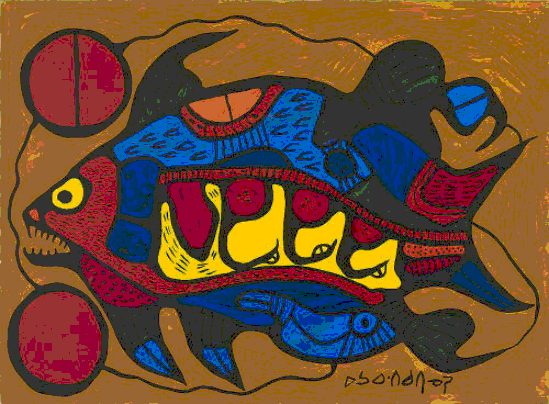

Norval Morrisseau - Untitled

Norval Morrisseau - UntitledThen along came Norval Morrisseau and Canadian aboriginal art was never the same.

In 1962 Morrisseau rocked the Toronto art world with imagery that had been inspired by the spiritual and mythological traditions of the Ojibwa, yet those images hadn't been created within the context of those same spiritual mores. On the contrary, Norval's paintings defied those traditions which dictated that Anishnabe stories and lessons were only to be shared within the Midewewin milieu and perspective.

But Morriseau was convinced that the ONLY way to keep the great Ojibwa (his words!) culture alive was to share the spiritual foundations on which it existed. He disregarded the will of the shamans and announced to the world that the Great Ojibwa were still alive and kicking!

But even as mainstream galleries began dipping their metaphoric toes into the world of Canadian aboriginal' art there was an ongoing debate among the artsy types in mainstream Canadian society about whether or not these new Indian drawings were real art or just symbolic extensions of traditional iconography.

Canadian Native Art Hit the Mainstream

The turning point was a 1972 exhibition of works at the Winnipeg Art Gallery by Daphne Odjig, Jackson Beardy and Alex Janvier called Treaty Numbers 23, 287, 1171. The numbers referred to the treaties that the artists' band members signed when they ceded their land to the Federal government.

The show moved Canadian aboriginal art from an anthropological phenomenon to an aesthetic possibility. Within months it lead to the formation of the Professional National Indian Artists Inc - labelled the Indian Group of Seven by Winnipeg Free Press reporter, Gary Scherbain, now owner of that city's Wahsa Gallery.

Within a decade Canadian aboriginal art was making a mark on the cultural landscape.

Carl and Daphne taught a short lived summer course for young artists on Manitoulin Island, which was then followed by courses sponsored by the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation. Many of those participants are either still painting or are working in music and theatre.

The following attended the Manitoulin summer school.

If you know of other young people who participated please email nokomis at native-art-in-canada.com

Nokomis - Illustrated Stories by an Ojibwa Elder

I was born in the bush north of Lake Superior at a time when the spiritual traditions of the Anishinaabe (that's Ojibwa to you!) were still practiced in a handful of communities.

After Morrisseau, The Indian Group of Seven made a deep impression on a new generation of native artists.