Native-Art-in-Canada has affiliate relationships with some businesses and may receive a commission if readers choose to make a purchase.

- Home

- Ojibwa Indian Crafts

Indian Crafts

Indian Crafts and Bush Skills

Indian crafts like baskets, snowshoes, moccasins, tikinogans and the like weren't made just to pass the time.

They were constructed to be used on a daily basis to hold food, keep warm, travel in dire conditions and generally stay alive.

Ojibwa children learned the ancient skills and knowledge that enabled them to survive and even thrive in the natural but harsh environment.

For the Woodland Indian, crafts such as canoe making, carving paddles, tanning hides, and making snowshoes were an integral part of their cultural experience. Many of the skills are still practiced today by folks who live in the northern communities.

|

Birch bark baskets like the one in the photo were one of the Indian crafts made by the hundreds to catch maple sap when family's moved to the bush to make their annual supply of maple syrup. Most other baskets were made to be more sturdy. Some had handles, other's lids and if the time was available women would often embellish the bark with elaborate designs. Birch bark could be patched if necessary and is amazingly strong and long lasting. If a birch tree fell in the forest today a hundred years from now the wood would have probably rotted away, but the bark would still be intact. |

|

Baskets were woven from willow, reeds and grasses in my part of the world. Kids were sent to harvest reeds for their mothers. The reeds were tied in bundles of ten or twelve and hung from rafters for a week or so to dry out of the sunlight which might have discolored them. I don't know why they did this because when it was time to do the weaving they soaked one or two reeds in water until they were pliable again and ready for use. There were always one or two reeds in the water waiting to be used next. |

|

Baskets woven from cedar strips were one of the Indian crafts that was disappearing even when I was a child. The reason was that a whole variety of containers could be bought at the store and preparing the strips for weaving was tedious. Nevertheless, every once in a while, some of the older women would work together assembling the cedar, splitting it into strips and sitting for days at a time weaving new baskets. Sometimes they dug up cedar roots, peeled them by pulling them through a V cut into the end of a board, then split them by slicing into one end and pulling off the strips. Cedar baskets smelled wonderful. |

|

Tikinogans gave mothers peace of mind. Whether the baby was on her back or propped up against a tree she could get on with her work knowing the child was safe. The Ojibwa design included a tall steam bent board that was secured over the baby's head. It served two purposes. The first was to prevent injury in case the tikinogan fell over and the poor child went face first onto the ground. The second was to hold up a thin piece of fabric to keep mosquitoes at bay in the summer and snow and wind away from the baby's face in the winter. |

|

Toboggans were one of the Indian crafts that made life easier living out in the bush. They were made using simple tools. Birch trees were easily splintered using a wedge and a heavy hammer and a crooked knife made short work of smoothing out the rough edges of the new planks. The boards were given a nice sheen with a bone polisher. The boards were heated in boiling water and bent over a log and tied with rawhide rope to keep them in place until the wood had dried. Traditionally they were assembled using plugs of wood and rawhide glue, but my Dad had access to screws from The Bay. Sometimes he used braided rawhide rope to pull the toboggans and sometimes he bought rope from the store. |

|

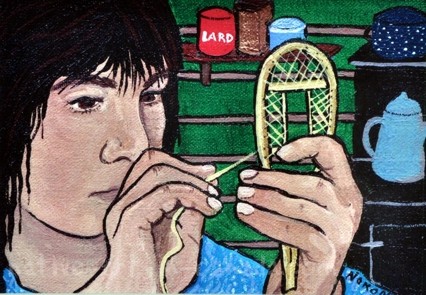

Snowshoes were another one of the Indian crafts that were a necessity of life there in the bush. This lady is making large, almost round so-called bear-paw snowshoes. But the Ojibwa were also know for the long narrow style with the upturned nose that were used when in bush with thick undergrowth. The bear-paw style was used in more open areas when the snow was particularly deep. It takes a little bit of practice to learn to walk easily on snowshoes and the next day beginners discover muscles they didn't know they had. I used to have to walk four miles to school and some days when I opened the cabin door the snow was eyeball high. That's what snowshoes were for!! |

|

Moccasins were made from deer and moose hide - the latter if it was available because the hide was thicker. Sometimes the maker would add an extra thick piece of hide to the sole to make the moccasin last longer but also to cushion the wearers foot if it was expected he'd have to travel over rough ground. The tops were originally decorated with porcupine quills but when glass beads became available in a multitude of colors they became the decoration of choice. The photo shoes a traditional Ojibwa moccasin with a puckered toe. This is the style that is copied by contemporary non-native manufacturers. |

|

Mukluks were basically puckered toe moccasins with ankle extensions that could range from six to fourteen or fifteen inches high. Long cords were secured at the ankle then wrapped around and around the lower leg and tied tightly to keep the snow out. Mom had seen some mukluks that had been made in the far north and she adapted that design because they had beaver fur tops that also helped keep the snow out. She took extra time to add beading because that was what love looked like. My brother and I got new boots each year because we were the oldest and the younger kids had to make do with the ones we had outgrown. |

|

Clothing was, of course, traditionally made from tanned hides and sometimes reeds were woven into capes or rain hats. But in my day the clothes we wore were made from a combination of traditional materials and what was available in mainstream society. Mom made our jackets from used coats she bought in town at church rummage sales - turning the fabric inside out to get the benefit of the fresh nap. But when she sewed them back together she added a beaded yoke and inserted a deer hide lining so that they were wind-proof and cozy. The yoke was cut from black velveteen she bought at The Hudson Bay store twenty five miles away. A cloth coat would not have kept us warm in the winter two hundred miles north of Lake superior. |

|

Tools were traditionally crafted from bone, rock, wood and shells or woven from strands of roots, wood fibres or animal hides. Some of those same kinds of tools were still being used when I lived in the bush seventy years ago. The steel bladed scraper my mother used to pull the remnants of flesh from the hides that she tanned was very similar to the one on the left. To weave the sinew back and forth across the snowshoe frames she used a carved bone needle type of device that was so smooth it slid easily in and out of the rough edges of the sinew. Sometime she also made fish hooks from bone. I'd also seen her use clam shells as dishes when she sorted beads. |

|

I was about to build this page when I suddenly realized that given that i was talking about Indian crafts, I should mention that we also did handicrafts to sell to tourists at the train station. Mom found that child size moccasins were in demand - especially ones that would fit babies. We also made small birch bark baskets. beaded necklaces and yes, toy canoes! I liked to make miniature snowshoes and sell them as decorations just before Christmas. They were a bit tedious but I found I could make one in an evening before bed. I don't remember what I sold them for but I was happy to have my own spending money. |

What's missing?

Well my sub-heading up at the top mentioned that this page was going to be about Indian crafts and bush skills. You'll have to wait for the bush skills part because I've run out of time today. I've had more to say about some Indian crafts than what will fit into the layout I designed above, so I made a page for them. Here's what I've written so far: