Native-Art-in-Canada has affiliate relationships with some businesses and may receive a commission if readers choose to make a purchase.

- Home

- The Woodlands School

Woodlands School of Life

A Lesson in How to Make a Difference

The Woodlands School of Art came into being following the successful launch of Norval Morrisseau's career in Toronto in 1962 and picked up steam after the successful showing of works by Daphne Odjig, Jackson Beardy and Alex Janvier a decade later in Winnipeg.

But the Woodlands School of Life is a work in progress...it's an ongoing commitment to change the conversation in the universe about what it means to be native.

You and I are having that conversation.

To understand the potential influence of contemporary artists of the Woodlands School, it's worthwhile noting that long before Europeans arrived on the shores of North America, First Nations people, for one reason or another, faced cultural catastrophes and it was often artistic activity that rode to the rescue!

It wasn't as if the community leaders got together and said "Hey, we have to do something about this." According to archaeological researchers, it was always some single person who realized that if he could focus attention on the symbolism that represented the cultural values and beliefs that had once been the foundation of the community, others would get the point and make their own contributions.

There have been three major bursts of artistic commotion within the prehistoric Eastern Woodlands culture.

The first took place around 1000 BC,

The second between 300 BC and AD300

The third from AD1000 to AD 1400

If you dug, (literally) into the pre-history of these groups ( the Adena, Hopewell and Southern Ceremonial Complex) you'd discover that the artistic and ritual bustle that took place was in response to cultural crisis - not just setbacks, but ALL-OUT-CALAMITY!

The increased artistic activity at those times had initiated and then became part of the revitalization of culture under EXTREME social and economic stress.

In prehistoric times the crisis may have been triggered by changes in climate, or perhaps disease or perhaps a challenge from a neighbouring community. But whatever it was, it resulted in severe challenges to the traditional means of livelihood.

Twentieth Century Calamity

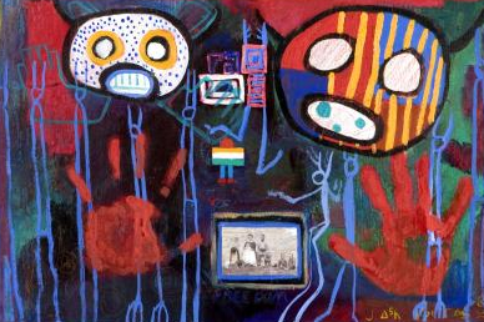

Jane Ash Poitras

Jane Ash PoitrasIn contemporary times the stress has come from legislated restrictions and acculturation that wiped out not only traditional means of livelihood but also the entire structure that Ojibwa society had been built upon.

According to A.J. Wallace's definition of revitalization and A. Trevelyan's analysis of archaeological data from pre-contact eastern North America, in prehistoric times cultural revitalization in response to crises was always initiated by individuals and those leaders developed a circle of disciples who spread the good word, so to speak. The leader's family and friends participated in the dissemination of ideas associated with the revitalization movement.

Morrisseau to the Rescue

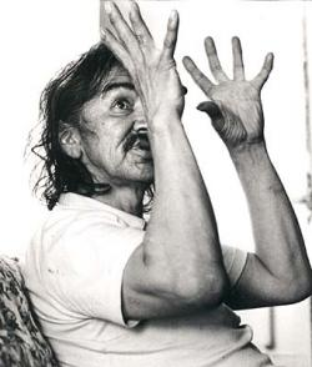

Norval Morrisseau is the modern leader who rode to the rescue of the Ojibwa culture in Canada.

He had been raised by his grandfather, Moses Nanakonagos (Potan) - a respected and powerful voice in the community and a traditional teacher - a chinshinabe. That's a word that refers not to just your average community elders who do their best to help the young make their way up and down the hills of life, but to those traditional teachers who are the caretakers of Anishnabe culture and sacred knowledge.

The eight year old Anishnabe boy - the good being - was removed from his home and put into a Catholic residential school.

It was not fun. Stuff happened.

But it was the Catholics themselves, centuries earlier, whose Jesuit brethren declared that if they were given a child for the first eight years of his life they could influence the man for ever.

Lucky for us...Potan got there first!

Because whatever damage was done to Norval, deep, deep down the Anishnabe boy survived. Despite the dysfunction, the addiction and the despair he lived with in his adult life, Norval understood that he was Anishnabe - a good being.

Whether or not he could give verbal expression to the idea, Norval also knew that the process of learning is essential to culture and so is the process of teaching culture.

Much of traditional Ojibwa culture has disappeared because the established methods of teaching children have vanished. Parents, grandparents, clans and spiritual guides are no longer the sole contributors to an Ojibwa child's value and belief system.

Traditional Ojibwa values, Ojibwa beliefs, everything about the Ojibwa way of life had been passed orally from one generation to the next for thousands of years.

But when children were taken to residential schools for years at a time and brainwashed by the dominant culture, they didn't have the opportunities to learn from the oral traditions of their elders.

One of the factors at play during the mainstream acculturation process was the fact that the fundamental concepts that supported the entire spiritual reality of the Anishnabe were controlled by elders, who, following the rules of their trade, were bound by strictures that forbade the public dissemination of their most sacred beliefs except within the circle of clans that controlled the entire society.

Morrisseau realized that without publicizing the Ojibwa stories, residential schooled youth would have no contact with the remnants of the Ojibwa culture that remained.

In school the christian teachers preached that their story was "the good word" and with the children out of reach the chinshinabe had no way of countering the dogma with their perspective of "good being".

Norval's idea was to put the imagery front and centre and get the conversation back on track. Despite the taboo, he began painting the stories of the Great Ojibwa.

After Morrisseau broke the prohibition to publicly display and discuss aspects of the traditional knowledge...and took much flak for doing so... sure enough, just like in prehistoric times, other First Nations' artists stepped up to the plate to make their own contributions. Daphne Odjig, Jackson Beardy and Alex Janvier held their show Treaty Numbers 22, 187, 1171 a decade later in Winnipeg and out of that the Professional National Indian Artists Inc was formed.

The Woodlands School of Art was born.

The Woodlands School of Art Bridges Cultures

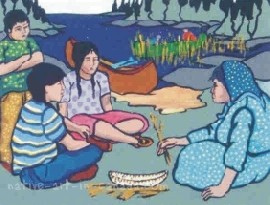

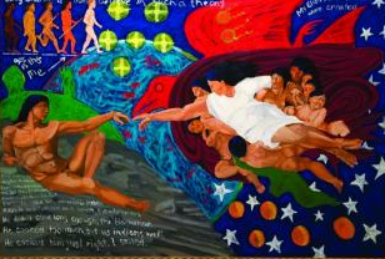

Jim Logan - "Rethinking the Western Front"

Jim Logan - "Rethinking the Western Front"Art doesn't teach religion and values, but art can make the viewer stop and think. A particular image might result in a question or two. It might impel some to look further for answers.

And art can certainly tell a story. For the contemporary Ojibwa the visual boost has allowed the oral culture to survive in a new way.

In prehistoric cultural revitalization, a process of reconciliation was also important to the long term stability of new ideas. That is, the message inherent in the art was that there had to be a way to reconcile the old ways with the new realities.

And because friction between neighbouring populations can be indicative of bigger problems that might affect entire regions, an important aspect of revitalization and the associated art activities involved formal and symbolic accommodation to make the message palatable (and understandable) to all...even traditional enemies.

The present day example is that the new Woodlands School combines traditional legends and myths with the reality that today, First Nations' culture exists within a mainstream milieu and artists include and use those parts of the Euro-American culture that enable their story to be heard...this web site for example :)

In the Canadian Journal of Native Studies IX 2, Amelia Trevelyan points out, that in ancient times art was used "to bridge, reconcile, re-educate and re-orient fellow native groups, however hostile. Today the challenge is to bridge the gap between entirely different cultures - First Nations people and Euro-Americas."

The grandfather of Canadian native Art.

The Influence of the Woodland School of Art

How the Woodlands School of art has been making a difference.

The Second Wave of Woodland Artists

These young artists followed in the footsteps of the Indian Group of Seven.

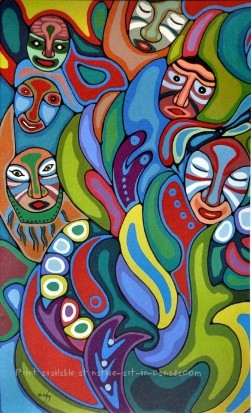

The imagery used in today's woodland art include physical transforamtion, spiritual communications and the merging of form and backgrounds.

Some discussion on the meaning of the symbols used in by woodland artists.

As the younger generations try their hand at painting, many take the Morrisseau imagery for granted...not realizing that it didn't exist in the modern world until he brought it forth.