Native-Art-in-Canada has affiliate relationships with some businesses and may receive a commission if readers choose to make a purchase.

- Home

- Ojibwa Children

Ojibwa Children

Traditional Education and Responsibilities of Ojibwa Children

Hundreds of years ago Ojibwa children didn't go to school, but that didn't mean they didn't receive an education.

Kids had practical lessons in every skill that they would ever need to live a healthy and happy life.

Parents, grandparents and other family members taught boys and girls age appropriate skills that allowed them to provide food clothing and shelter for themselves and others, and do so in a way that didn't harm the environment and didn't interfere with the health and well-being of other people in the community.

Although there was a distinct division of labour in the Ojibwa culture...men provided food and protection, women provided shelter, clothing, cooking and much of the child rearing...when growing up, Ojibwa children were taught the fundamentals of all those skill just in case they needed them to survive.

During 1930's and 40's my family lived on a trap line in the bush 200 miles north of Lake Superior. In those years, any self-respecting six year old knew how to set a snare to catch a rabbit for dinner, bait a hook, or set a fire. And it was a rare twelve year old who couldn't hunt with a rifle. . . alone . . for days at a time.

Some Responsibilities Depended on What Clan You Belonged To

As children we also had responsibilities to the community as a whole. Those responsibilities depended on which clan we belonged to.

The clan system that governed traditional Ojibwa society was known as dodem. There were seven clans (and seven subsections) and each clan had a responsibility to the society as a whole - care giving, protection, foresight or spiritual guidance, for example.

Also, each clan nurtured a special gift that members were expected to bestow when they saw the need. For instance, the gift that was given to members of the deer clan was kindness. Mothers of the deer clan would teach their children the many ways of being kind, because, throughout their lifetime, whenever they recognized a situation in which a little kindness might diffuse an argument or lift another's spirit, it was their responsibility to find a way to interject a little compassion or gentleness into the situation.

Members of the bear clan gave of their strength when it was needed. . . not just physical strength, but clan members were trained from childhood to be strong enough emotionally and spiritually to take a stand on the side of what was good and what was likely to work for the communal good rather than for what might be convenient or profitable.

Whatever were we heathens thinking by teaching our children to consider the well-being of others and the community as a whole!!?? Obviously that was bad because the Department of Indian Affairs and the churches outlawed the system.

Huh?

Ojibwa Children's Daily Chores

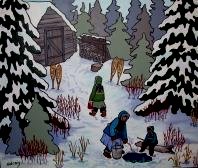

As kids we were expected to help out by hauling water, bringing firewood into the cabin, or gathering food. Dad's income was from trapping but he hunted and fished for food, too, and made sure my brothers also learned those skills. He taught them how to track animals in the bush, how to gut a large animal and haul it home and how to build shelters on the trail.

Mom was in charge of things domestic...cooking, cleaning and looking after us kids. She taught me how to gut, remove the feathers and cook ducks and geese, how to scale, clean and cook fish, scrape and tan hides and even how to make soap!

All of us kids were sent out in the bush to bring home certain things Mom would want to use when she cooked a meal...sometimes certain roots or leaves, always berries in season. All Ojibwa children of my era who were living in the bush knew how to recognize the various plants and roots that were safe to eat.

We didn't have to gather those foods because we were poor...Dad sold his furs and we had money to buy anything we wanted either from the general store or from Eaton's catalogue. But until I started school we were never closer than twenty five miles to town so it was just practical to go outside and see what was tasty.

Wash Day Chores

I hated

wash days because my brother and I had to carry about twenty heavy pails of water from the

lake. It was hard work in the summer but many times more difficult in winter when we had to start the chore by chopping a hole through the ice. When we'd hauled all the water that was needed we were then expected to catch a couple of fish through the open hole.

Sometimes the ice would be so thick that it wasn't even possible for my Mom to get through to the water so we'd have to melt snow instead. A pail full of snow melts down to only a few inches of water so the twenty pails of water needed for a summer wash translated into fifty or sixty pails of snow in the winter.

My mother never allowed us to get the snow from around the cabin...that was "yellow snow where the dog's pee'd" she said!

We were supposed to go out into the middle of the lake to bring in fresh clean snow. She regularly stuck her head out the door to see where we were coming from because I must admit we'd been known to bring in the odd bit of yellow snow.

One day my brother and father were off on a hunting trip, and I was

expected to bring in enough snow by myself to allow my mother to do the

wash! How unfair! But that was my job and that's all there was to it.

Necessity being the mother of invention I decided that if I dragged a blanket out to the middle of the lake I could pile at least ten pails of snow onto it and drag it all back to the cabin...making only five or six trips instead of fifty or sixty.

Good idea, right?

And I'm not stupid.

I knew enough to use my brother's blanket instead of my own because I was sure he and Dad would be gone on the hunt for a couple of days at least and no one would be the wiser. Of course, with that timetable in my mind I thought it was OK to leave the soggy blanket in a heap in the corner when I finished my chore.

But as fate would have it, the hunting party took down a deer on the first afternoon and came home by nightfall.

Oops!

Everyone was mad at me!

My mother yelled. My brother screamed and my father allowed him to have my blanket. I had to sleep on the floor in my parka beside the stove.

How cruel and unjust when I had invented such an efficient method of bringing in snow for the weekly wash!

But now that I've got to tell my side of the story seventy years later, I'm beginning to feel a bit better.

Ojibwa Children and Discipline

It's hard to realize it when you're a kid, but most of those rules that parents and teachers impose on children are to teach them what it takes to create a grown up society that functions without too many disruptions. Like when you were a kid, who knew that the reason you couldn't whack your brother when he did something mean was that if you were still whacking people thirty years later you'd be put in jail?

Not that I whacked my brothers. (much)

One of the rules my brothers and I had to live with had to do with appropriate behavior in a crowded tent in the middle of winter. Before I went to school my parents and three kids lived in an 8' x 10' tent when we were on the trap line in the winter. No, it wasn't cold because the walls were banked with snow which made good insulation and we had a small tin stove inside that was vented through a pocket in the back wall.

The thing to know is that the tent was warm...but it was crowded.

The rule was we had to sit quietly on the sleeping cots and not play around. You know how it is when kids play around, right? Things can get out of control and in the tent in winter that was dangerous because of the hot stove. Besides the fact that we might bump into the stove and burn ourselves there was the good possibility that we'd burn the whole tent down, too. So...no fooling around in the tent.

If we wanted to play we had to go outside. Our parents didn't care if it was midnight we were still allowed to go outside and blow off some steam.

The thing is if we did start to fool around we'd be given ONE warning.

If we did it again (or even looked as if we were going to mess around again) we found ourselves in boots, coats, mitts, hats standing outside the tent . . . and the door was tied closed from the inside so we couldn't get in!!!

It didn't matter that it was 30 degrees below zero with a howling wind or that it was eleven o'clock at night. The rule was, "Don't fool around in the tent."

We could sulk, cry, screech, beg or threaten to run away.

Nobody cared. Nothing happened.

It was only when we were playing quietly for a suitably long time that the door was finally opened.

Nothing was said. No reprimands. No nagging. Just the opportunity to sit quietly on the sleeping cot.

- In a Snit

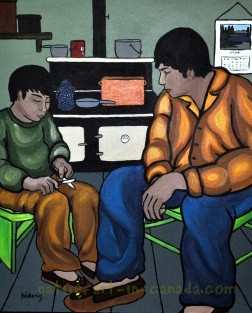

- Time for a Chat

- New Boots

- Ojibwa Canoes

- Ojibwa Tea

- Ojibwa Food

- Home

Here's a few more examples of sibling rivalry...

And here's some more links to the Ojibwa culture