Native-Art-in-Canada has affiliate relationships with some businesses and may receive a commission if readers choose to make a purchase.

- Home

- Norval Morrisseau

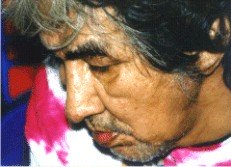

Norval Morrisseau

Grandfather of Canadian Native Art

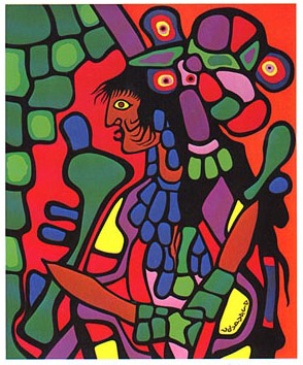

Norval Morrisseau - The Great Mother

Norval Morrisseau - The Great MotherNorval Morrisseau is the grandfather of native art in Canada.

His vision of himself and his people created the possibility that native artists would have a major impact on the cultural revival of Ojibwa values. And he lead the parade of hundreds of young native artists into the conscious mind of the Canadian public.

Born on the Sandy Point Reserve near Beardmore, Ontario, March 14, 1932 Morrisseau was raised by his maternal grandparents.

Moses Nanakonagos (Potan) and his wife Veronique, lived on the Gull Bay shore of Lake Nipigon.

This was a traditional arrangement. As the eldest of seven boys it was expected that he would be the link between his grandparents and his own generation. The tradition benefited both participants. The younger generation was schooled in the cultural conventions of the Anishnabe and the older generation benefited from the young muscles.

Potan was a Midewinini and Jissakan - a shaking tent seer. Morrisseau learned stories, responsibilities and spiritual concepts from his grandfather but in his eighth year was taken away to a Catholic residential school in Fort William.

Norval Morrisseau and the Residential School

It wasn't a good experience for the child and in the end it resulted in only a 4th grade education. Too bad in one sense...but centuries earlier it was the Catholics themselves through the mouthpiece of their Jesuit brethren , who had declared that if they were given a child for the first eight years of his life they could influence the man for ever.

Lucky for us...Potan got there first!

When Norval left school early he started making drawings of the prehistoric rock art and of the images he had been shown by his grandfather on the Medewiwin birch scrolls.

The elders told him that this was taboo.

Wrong Man Acknowleged at Agawa

But in 1952, while still in his teens, Norval Morrisseau met Selwyn Dewdney, a former missionary who was investigating the prehistoric rock pictographs scattered throughout the region. Morrisseau guided Dewdney to many of these sites and decoded their meanings for the researcher. To demonstrate the significance of the imagery he shared many of the Ojibwa myths and legends with the investigator.

Unfortunately it was Dewdney who became known as the expert on the subject.

In 1965 Ryerson press published Norval's stories, Legends of My People, The Great Ojibwa. The book, now long out of print, was edited by Dewdney and illustrated by Norval Morrisseau. It was presented to the world as a book of stories for children.

There is a blasphemous bronze memorial to Dewdney imbedded into the Lake Superior rock face at Agawa - a sacred site to the Ojibwa. Like any man, Dewdney deserves acknowledgement for a lifetime of hard work, but not at a sacred First Nation's site.

What were you thinking, guys!!!!

Please!

Someone - remove it!

Visioning Another Way of Being

At 19, Norval developed tuberculosis and was sent to a sanatorium in Fort William. To pass the time he again began drawing the same forbidden images that got him into trouble with the elders a few years previously.

A doctor, not knowing of the taboo, encouraged him to paint. At this time Morrisseau had a series of dreams and visions that he said called him to be a shaman-artist.

He decided that the cultural images of the Ojibwa could only be made relevant to contemporary minds with a contemporary medium. He began painting in earnest no longer caring about the taboo.

Eventually, with the tuberculosis under control, he moved back to the reserve, and began exploring old canoe routes, paying particular attention to the rock petroglyphs common in the area.

Thunderbird - Red Lake Museum

Thunderbird - Red Lake MuseumIt was during this time that he had another dream. In it the manitous came to him, and in a traditional naming ceremony declared him to be Miskwaabik Animiiki, Copper Thunderbird.

From that time on, Morrisseau wrote his spirit name in syllabics (taught to him by his wife) on all his paintings.

Copper can be found in rare surface deposits on the rocks of the Canadian Shield and is significant to the Anishnaabe. Archaeological evidence indicates it was mined and used for ceremonial and ornamental purposes at least a thousand years before European contact.

The Spiritual Power of the Anishnabe

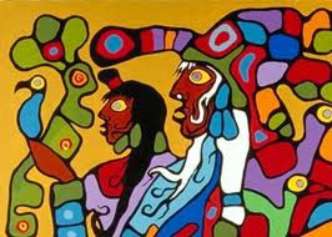

Miskwaabik Animiiki began painting images that represent the spiritual guts - the source of power - of all living beings whether human or animal. His images portrayed an x-ray anatomy with spirit power lines radiating from the spines of the creatures he portrayed.

"My paintings are icons - that is to say, they are images which help focus on spiritual powers, generated by traditional beliefs and wisdom," he said.

Without the artistic elegance, the same features are seen on the

Midewiwin birch bark scrolls of rites and song mnemonics. They are also

roughly suggested in the rock petroglyphs all over the woodlands north

of the Great Lakes.

In the beginning there was no market for Norval Morrisseau's paintings or any other contemporary native artist's work, for that matter. The mainstream art world had always excluded the prehistoric and functional works by native artists, and the anthropology versus art debate continued well into the 1980's.

Even the Department of Indian Affairs catered to the tourist trinket market which included beads and buckskin, buffalos coming out of clouds and plastic totem poles cast in Hong Kong.

So Norval lived in poverty on his reserve, bartering drawings and paintings for food and other supplies.

The Big Break

Despite all that, the paintings of Norval Morrisseau stormed the Toronto market in 1962.

In the summer of that year Toronto gallery owner, Jackson Pollock, had been teaching painting in northern Ontario. Pressed by friends, Pollock begrudgingly made an effort to visit Morrisseau's home to see the Indian artist he'd been told about.

He was stunned by the combination of imagery and colours in Norval's work. Until the artist envisioned the possibility, nothing like it had existed in the world.

Pollock arranged a show of Morrisseau's work in Toronto and the artist exploded onto the contemporary art scene on opening day. Every painting sold.

But Norval Morrisseau Was Still Getting Flak at Home

While he was lauded in the streets of the big city, he was still criticized at home for revealing sacred knowledge though his imagery.

But by then Norval Morrisseau was sure of himself.

He defended his work. His point was that in the modern world there had to be a new way of communicating the spiritual essence of the Anishnaabe world to the Anishnabeg themselves.

Five hundred years of contact with the dominant culture had all but destroyed the foundations of the Ojibwa's perception of themselves and their place in the universe.

Norval wanted to restore cultural pride and spiritual awareness to the largely Catholicized members of his community. He felt that the spiritual renaissance could only happen if there was a way to bring the traditions forcefully into present day conversation.

Note: There have been three separate instances in prehistoric Eastern Woodland culture when there was an artistic and ritual renaissance in response to cultural catastrophe.

Traditionally that knowledge had been passed on orally. The Anishnabe call it bzindamowin - a way of learning by listening. It is knowledge that develops from hearing cultural stories...not just one story and not just one time. Knowledge is acquired when many stories, intrinsically related, are repeated over and over until they are heard in a way that finally makes them applicable to oneself. Within the stories are the lessons and the edicts to living a good life. Anishnabe means the good being . The stories help us become Anishnabe.

Norval Morrisseau re-started the conversation. He spoke in a way that others could hear. They may not have understood...but they sat up and listened.

Other artists quickly chimed in. Daphne Odjig, who had been painting in the European style all her life, felt moved to share her stories and it was as if the "language' of her imagery changed to meet the cultural context. Jackson Beardy, Eddy Cobiness, and Carl Ray made their contributions. Others saw their imagery and it resonated in the heart of their being. They too found that they had something to say about the Anishnabeg.

Norval Morrisseau died December 4, 2007.

During his lifetime he changed the conversation in the universe about what it means to be Anishnabe.

I loved you, Norval, (and thanks, Gabe, for your contribution).

Norval Drew from a Well of Ancient Woodland Imagery

Although the training, lifestyles and creative motivation of contemporary native artists differ profoundly from their ancient counterparts, today's Woodland art is actually sourced by traditional artistic representations used by prehistoric Eastern Woodland Indians.

Daphne Odjig- Grandmother of Native Art in Canada

The grandmother of Canadian native art, Daphne Odjig painted long before there was such a thing as a contemporary native art movement on either side of the 49th parallel.

In 1973 seven native artists gave birth to the Professional National Indian Artists Inc.

Influence of the Indian Group of Seven

Individual members of the group went back to their communities and influenced another generation of legend painters.

Short biographies of native artists who began their careers after Norval broke the ice.

The influence of the Ojibwa on Canadian native art.