Native-Art-in-Canada has affiliate relationships with some businesses and may receive a commission if readers choose to make a purchase.

- Home

- Wild Rice

Harvesting and Processing Wild Rice

Wild rice, known as manomin to the Ojibwa, was a staple food in the Eastern Woodland Indian culture for more than a thousand years. Although it's commonly referred to as wild rice, it isn't technically a rice. Manomin is a grass of the family Gramineae, the genus Zizania...and it grows only in water. The two main species that have been traditionally used as food are zizania aquatica (or palustris) and zizania aquatica angustifolia.

At one time wild rice seems to have grown over a large portion of North America that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Rocky Mountains and from the Gulf of Mexico almost to the shores of Hudson Bay. But the boundary lines can only be called approximate because there were many areas within that territory where the grain grew very little or not at all.

The natural habitat of the manomin was made much smaller with the influx of European settlers because they unwittingly disturbed the seed beds near the lake shores.

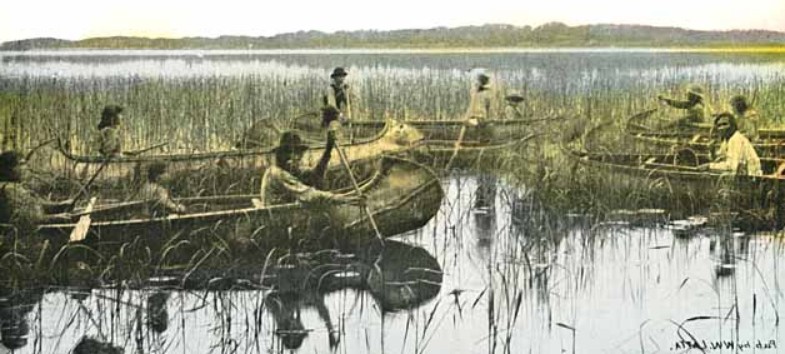

The whole process of harvesting the crop is called manoominikewin in Ojibwa or ricing in English.

The kernels are collected by beating the ripening heads with sticks so that the seed falls into a canoe or flat bottomed boat. Back at the shore the wild rice is first dried in the sun, then parched by either smoke drying or scorching in large metal kettles. The chaff is threshed and then winnowed with large multi-purpose bark trays.

Germination and Growth

Wild rice is an annual plant that requires reseeding each year. The stalks from the previous season die down below the water level and the new growth appears in the same spot giving the impression that there is a perennial root system that is the source of the current year's plants. But that isn't so.

Germination begins when the snow melts and the longer hours of sunlight gradually warm the water. The stalks don't emerge above the water until July and if there's been no water contamination and the seed beds have been left undisturbed - not to mention the weather being 'just right' - the upper stalks mature to a pyramid shaped panicle that takes about ten to fourteen days to unfold in late August. The top most grains ripen first and the maturing process gradually continues down the panicle. That means that the seeds can be harvested over time...occasionally the canoes will go through the rice beds three times in a season, but usually two times is adequate.

Binding the Rice

Years and years ago, prior to harvest, women were sent out in canoes to bind the seed heads of the wild rice into bundles. Each family bound the heads in a different manner as a way of declaring ownership to that particular stand of wild rice.

They wrapped the panicles in special patterns or used a particular type of binding material...strips of the inner bark of cedar, strips of basswood bark that was first softened then pulled through a hole in the bones of a bear's pelvis (!) or even burlap that had been unraveled from a gunny sack.

Whatever material was used it was wound into a large ball...sometimes a foot in diameter. And it wound that it would unwind from the inside like a modern day ball of binder twine!

Community members acknowledged particular binding techniques and property was generally respected. In this way, the fall wild rice harvest was somewhat like the spring maple syrup harvest as each family had a share of the rice field and a share of the grove of maple trees.

Tools for Harvesting Manomin

The only tools need to harvest rice are those to move the canoe or flat bottomed ricing boat and to knock the ripe kernels into it. Paddles or poles were used to move the canoes through deep water but a long pole that was forked at one end was used when the boats arrived at the rice beds. The fork was able to grip the soft muddy bottom without disturbing the tender root bed. Many, many years ago the clans would not allow simple poles within the rice beds because they caused too much damage to the root system.

Knocking the Rice

Wild rice is harvested by threshing the stalks to extricate the kernels. This was referred to as knocking the rice. When Europeans began harvesting rice they introduced mechanical combines, but even now most Ojibwa harvest rice by knocking.

Until it's parched, the pointed beards on the kernels present a hazard so ricers wore high boots or long socks that could be pulled up over their pant legs for protection...not just from the sharp kernels but also from an insidious little rice worms that pack a sharp bite.

The technique for knocking wild rice is to simply hold one stick in each hand and as the boat moves forward the harvester reaches to the right or left with one stick, pulling as many stalks as possible over the side of the boat. Then the second stick is used to knock a sharp blow on the first stick so that the seeds fall into the bottom of the boat. Sounds easy, but the stalks have to be at a proper angle to the gunwale and the blow with the stick must be aimed in the right direction, otherwise the stalks may break off and then a second harvest wouldn't be possible.

If the rice is perfectly ripe it practically explodes into the boat in one stroke, but sometimes the sheaf has to be knocked a second or third time.

That done the ricer reaches over to the opposite side of the boat to harvest wild rice from there.

Drying the Manomin

To avoid mildew forming from the moisture that occurs naturally in the kernels, wild rice must be dried as soon as it comes off the lake.

But when more rice has been harvested than can be processed immediately it's preserved in it's green state by keeping it in water for up to a week.

Wild rice continues to ripen after harvest but it must have air, sun and sometimes even the heat of a fire to get rid of moisture before parching. It can be spread out a few inches thick on canvas, hide or reed woven mats to dry. While it's spread out the rice is picked over to remove pieces of stalk, dirt, rice worms or weeds that have fallen into the boat.

Constantly turning the rice while drying helps the drying process.

Sometimes conditions are such that fire drying is necessary. Years ago a long flat scaffold was built several feet over a slow burning fire. Woven mats were laid on the scaffold and the rice spread over top of the mats. Some of these drying racks were 10 or 20 feet long and required several small fires to spread even heat.

Before Europeans introduced large iron kettles, First Nations people always fire dried their rice.

Parching the Manomin

If the wild rice is not fire dried it must be parched (slow roasted)

to preserve the kernels for storage and make them edible. Parching

destroys the germ (kids...that is the living inner kernel of the rice

seed, not a disease kind of germ!) and prevents the seed from sprouting

so that it can be kept indefinitely. Parching also hardens the kernel

and causes the hull to become loose so that it can be broken off and

discarded. Also, parching scorches the long barbed end of the kernel and

tends to destroy any foreign matter left over after the initial

cleaning...like those creepy little worms!

The Ojibwa preferred to parch their wild rice as soon as possible after the harvest. Left for two days the rice turned black. Left for three days it had to be parched immediately or it would turn coal black. If the rice was dried and parched immediately after coming in from the water the rice was said to be green. Green rice simply had to be put in hot water and soaked to be ready to eat.

Once they became available for trade, the Ojibwa parched their rice in large cast iron kettles. The vessel was propped on it's side with rocks or logs over a slow burning wood fire. Skilled at controlling the burn, the Ojibwa ricers never allowed the fire to get too hot. They could parch rice to perfection even in the dark.

Up to a half bushel of rice could be parched at one time. Sometimes the Ojibwa called it scorching. The wild rice was stirred constantly with a special cedar paddle in a lifting motion to keep the bottom kernels from burning. Roasting times varied from fifteen to twenty five minutes for small batches, but up to an hour for larger quantities. The time also depended somewhat on the container used to do the parching. Cast iron kettles are slower than galvanized wash tubs but they distribute the heat more evenly making the job easier.

Hulling the Rice

After parching the wild rice must be hulled to remove the tight

fitting chaff from the kernel. The traditional methods of breaking the

chaff were either flailing with a flat stick, churning or treading.

The most common method in prehistoric times was to tread the wild rice in a small pit dug in the earth which would have either been clay lined or covered with rawhide to contain the rice. More recently the pit (which was 2 - 3 feet in diameter and perhaps 18" deep) was lined with wooden slats making it look much as if a barrel had been sunk in the ground.

All methods involved really hard strenuous work. The job of treading rice usually belonged to the men...or a cadre of boys who would take turns walking on the grains. They had to wash their feet and wear new or at least very clean moccasins. To help the workers maintain their balance a couple of poles were installed either side of the pit so that the treaders could hold on tight.

From watching the process as a girl I know that a strong man can hull a batch of rice in about fifteen minutes. It's exhausting work because the process is continuous as newly roasted

rice keeps arriving. It was an exceptional man who could last more than

two hours. Boring, too. But the old women would coerce some of the young bucks to take turns and then make sure that a few young women were on hand to egg them on. Gullible, or what!

Hulling was the first process to be mechanized when wild rice production became a commercial venture.

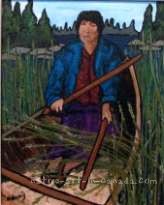

Winnowing the Manomin

After hulling, the rice and broken chaff were emptied in small amounts

into shallow trays for winnowing. It could either be spread on mats or

blankets and fanned by hand, or quantities put into large shallow

birchbark trays which were agitated with a paddle to cause the chaff to

rise to the top and be lifted off by a passing breeze. Alternately the

wild rice could be tossed into the air and repeatedly caught again like

this woman is doing. It's a learned skill - sort of like flipping pancakes with a frying pan.

Storing the Rice

Traditionally the Ojibwa stored provisions, including wild rice, underground in containers. Processed rice unexposed to moisture keeps indefinitely. The skin or bark vessels, and the methods of packing, ensured that the contents would stay dry.

A variety of animal skins...taken off almost whole for this purpose and sewn into a sack...were used to hold wild rice. A fawn skin was used as a measure between some traders for example.

But bark containers were more common...either woven bags made from the inner bark of cedar trees from birchbark. In my day the latter were known as makakoon and could be sewn tightly shut to preserve the contents which could be wild rice, berries or even preserved meat.

As much as one-third of the rice harvest was packed in birchbark containers and buried in a pit dug below the frost line.